By Dr. Sue Onslow, Senior Research Fellow, ICwS

It’s election time again in Zimbabwe, with the nation going to the polls on July 31st. Elections have a pretty combustible track record in the Zimbabwe political space. So much of today’s vociferous media coverage and comment makes repeated reference to Zimbabwe elections since 2000. But the 1980 vote – the final part of the Lancaster House settlement, with its crucial aspect of multi-party elections before internationally recognised independence – was no exception to a story of a hotly contested multi-party election against a backdrop of violence and intimidation, intense international media interest, and anticipated enormous significance of the outcome for the wider region.

I’ve just done two interviews with former Commonwealth officials who were intimately involved in those first universal franchise Rhodesia/Zimbabwe elections. They pointed out the Commonwealth blazed a trail with the process of election monitoring long before the UNO, SADC or the AU. Sir Sonny Ramphal, the Secretary General of the time, clearly appreciated that elections had to be seen to be free, and fair (or to use today’s terminology, free-ish, and fair-ish) and – crucially – credible. And that the Zimbabwe people would choose ‘self-government’, not necessarily ‘good government’.

Taken together with the available material from the Commonwealth Secretariat archives, the interviews outlined how, with limited resources, but extraordinary connections and resourcefulness, a small team of election observers arrived in Zimbabwe in January 1980. That the team had to have an experienced and authoritative diplomat as leader – Indian diplomat Rajeshwar Dayal had led the UN mission into the complex Congo crisis in 1960-1. Rhodesia/Zimbabwe had experienced a brutal bush war, and spiralling violence as a political language. The business community had become insidiously corrupted through evasion of international sanctions since 1965. A strategy of survival, yes, but this meant progressive corruption of corporate ethics and a lasting malaise. All this has disturbing similarities with Zimbabwe’s current political culture, corrupt business practice, and militarisation and militia-sation by ZANU-PF of the structures of governance & the formal and informal economy.

These Commonwealth observers criss-crossed the physically vast country (the size of France). The observers maintained standards of strict impartiality, maintaining lines of communication with formal authority, and all political parties. Understanding that ‘Facts are facts. But Perception is Reality’, they knew information and transparency was key, and to make sure that the two connected – as much as possible. Derek Ingram, the immensely experienced Commonwealth editor and journalist, was given the remit of media assessment. These Commonwealth observers also knew that intimidation could be overt, or subtle and covert; but there was a limited amount they could do about this. Polling then lasted for three days – the allocated single day does not look realistically possible, but there have been rhetorical reassurances that every single vote will count, so people in line at the formal closing of the poll can reasonably expect to vote. But – and it is a vital But – in 1980 there was a clear understanding that, as election observers, they were not referees. They were there to monitor the process of an election, not to deliver a particular result. That fact is getting lost in public perception and the current media hype around the role of SADC and AU election monitors.

So there are strong echoes of the past as Zimbabweans go to the vote. In 1980, many in Rhodesia/Zimbabwe felt cheated by the election outcome; there were a number of coup plots (including one to blow up the independence motorcade of international leaders and dignitaries, which included Prince Charles. It was very nearly implemented.) But in the end, compromise and accommodation triumphed: newly independent Zimbabwe had its first coalition government, which included rival political leaders.

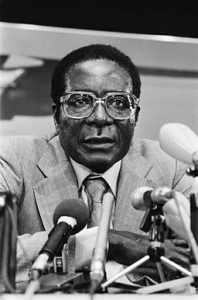

Looking through that lens of history, from these interviews, also underlines that state and society in Zimbabwe are still undergoing a constant process and dynamic of change. This is the reality of the politics of transition. Mugabe, then as now, is an iconic liberation leader. He has not changed, and in fact has been remarkably consistent; unfortunately – for him – the state of Zimbabwe and the rest of the world has. We have now moved to a post-Mugabe world. Listening to his speech on Sunday of a ‘Do or Die struggle’, I was left with the overwhelming impression of an (very) elderly and weary boxer, battered against the ropes; given his age and very poor health, was the implicit subtext ‘Do and Die’?

Another of the many lessons from 1980 is ‘Political opponents should not be demonized.’ If you do that, it cuts down appreciation of their rationality. ZANU-PF is a coalition, in 1980 and now. You may think indigenization legislation mad, bad and dangerous – but to those in ZANU PF with an obstinate national focus on people’s sovereignty and entitlement, it makes eminent sense in political terms. (We will just leave the question of political and personal opportunities of self-enrichment out of it.) Unfortunately, in today’s regional and globalised political economy, and for a country that desperately needs FDI, it is bonkers. The international investment community wants, and needs, a stable policy environment. It can be done. The managers of the Zimbabwean political economy moving from that bush war to peace time faced enormous challenges, but the 1980s proved a remarkable period of economic regeneration and human development. ZANU PF can take enormous credit from that; my two interviewees did remind me in 1981 Zimbabwe received a massive US$365m multilateral developmental aid programme. But too many people did not benefit – and the politics of expectation is a dangerous thing. The 2013 election result is going to take time to emerge, and longer to deliver people’s basic needs. There is a balance to be achieved between social rights and human rights, democracy and development.

Structures and political and social attitudes are perennially important. Zimbabwe has a new constitution (as in 1980), but needs constitutionalism – the practice of governance, and that means all sides agreeing to the explicit and implicit rules of the game. Violence remains part of the political discourse, so fear has been a repeated, and conditioning factor. All this makes the commitment, engagement and activism of ordinary Zimbabweans all the more extraordinary, and let’s hope they get the election result they deserve. The chances are dramatically improved from 2008 of a more credible result. The appointment of General Obasanjo as leader of the AU monitoring mission is very good news – an African elder who himself has overseen transition to democracy in Nigeria; and his credentials as a ‘good Commonwealth man’ are 24K gold. And as in 1980, there is also strong regional pressure from behind the scenes.However, given power realities within the Zimbabwean state, the chances are the final outcome will be a re-booted coalition. But if the process and outcome is messy, partial and imperfect – which it will be, let’s be realistic – Zimbabweans will work with it. Of that we can be sure. Just as in April 1980.

[View the story “Zimbabwe Elections 2013: Free-ish and Fair-ish?” on Storify]