Dr Eva Namusoke, Postdoctoral Research Officer

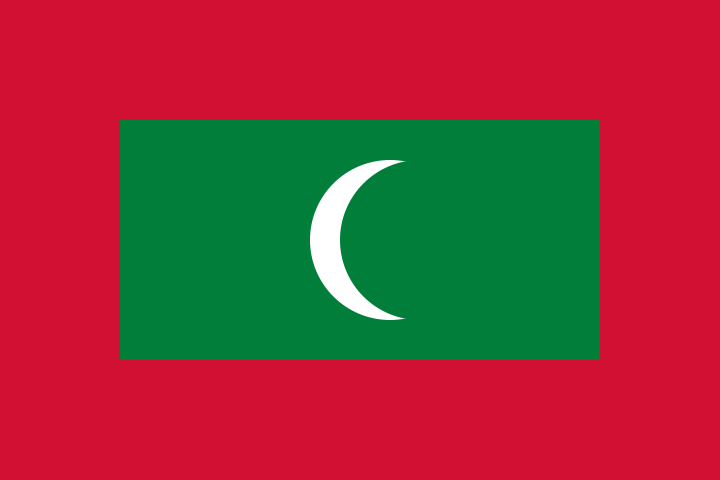

On 13 October 2016 the Maldives became the third country to leave the Commonwealth. The decision came after a number of years defined by a frosty relationship with the Commonwealth, centring on allegations of undemocratic practices, human rights abuses, and more recently corruption on the small island nation. The decision was seen as a preemptive move, as the Maldives was facing calls for suspension by the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative. An official statement by the government of the Maldives read in part:

‘Since [2012], the Commonwealth Ministerial Action Group (CMAG) and the Commonwealth Secretariat have treated the Maldives unjustly and unfairly. The Commonwealth has sought to become an active participant in the domestic political discourse in the Maldives, which is contrary to the principles of the Charters of the UN and the Commonwealth.’

A further statement by the Foreign Minister of the Maldives also included direct criticism of the CMAG and Commonwealth. Mohamed Asim, argued that the who had ‘become embedded in the political discourse of smaller member states. This has helped the Commonwealth leverage its way into international diplomacy.’ This is a particularly pointed criticism of a Commonwealth that has struggled to maintain relevance in a crowded international space. Indeed, the Commonwealth had been actively engaged with the Maldives for much of the last decade. A number of individuals interviewed for the Commonwealth Oral History Project, including Matthew Neuhaus, Karen Brewer and former Secretary General Sir Don McKinnon reflected on the political situation.

A further statement by the Foreign Minister of the Maldives also included direct criticism of the CMAG and Commonwealth. Mohamed Asim, argued that the who had ‘become embedded in the political discourse of smaller member states. This has helped the Commonwealth leverage its way into international diplomacy.’ This is a particularly pointed criticism of a Commonwealth that has struggled to maintain relevance in a crowded international space. Indeed, the Commonwealth had been actively engaged with the Maldives for much of the last decade. A number of individuals interviewed for the Commonwealth Oral History Project, including Matthew Neuhaus, Karen Brewer and former Secretary General Sir Don McKinnon reflected on the political situation.

The Maldives was initially viewed as a success story following the 2008 election of President Mohamed Nasheed. However, the situation was to change in early 2012 with the arrest of the chief justice of the criminal court, himself a member of a judiciary with ties to Nasheed’s predecessor. The 2012 arrest bolstered the opposition in the Maldives and sparked clashes between security forces and the government. As a result, the president was forced to resign and was replaced in delayed 2013 elections by Abdulla Yameen. The period that followed saw deteriorating human rights conditions and the arrest and conviction of Nasheed. Sir Don McKinnon’s April 2014 comments on the ongoing situation were marked by a frustration at the developments, no doubt influenced by the fact Sir Don had personally used his ‘good offices’ in working with the Maldives over a number of years leading to the 2008 elections and that preparing for those elections was one of his last actions in office. For Sir Don, the problem was a lack of follow-through with the Maldives after President Nasheed’s election, particularly by Sir Don’s own successor as Secretary General.

In response to the events in early 2012, Sir Don was invited by the Commonwealth to act as special envoy to the Maldives. Sir Don’s description of the work presented it as very much a continual process, evidenced by the fact he made 10 trips to the Maldives, meeting and working with the Waheed government. Hugh Craft, an Australian diplomat and Director of the International Affairs Division in the 80s was a member of the Commonwealth Observer Group sent to the Maldives for the 2013 elections. Interviewed in March 2014, he too expressed disappointment at the turn of events in the country, adding,

‘With the amount of resources the Commonwealth has put into the Maldives over the years – particularly with Don McKinnon’s exercise – member governments are asking with so little practical outcomes whether it is all worth it. Certainly, my own government is asking that question.’

For the Maldives, it appears that what was once seen as Commonwealth advice and assistance became perceived as Commonwealth posturing and interference. What was once a Commonwealth success story must now be moved to the margins where fellow former Commonwealth nations Zimbabwe and The Gambia stand.